7

I have matured and become an older, different person since the last time you heard from me. If that required for my age to increase numerically, I am sure that happened too. I have grown years. I feel it in my spine. I had been taking a break from my career and other such adult responsibilities, frolicking in the sun and out-grown lawn, tending to flowers and butterflies, when it happened- this exponential maturation which is usually motivated by existential dreads. I had put myself at a distance, so I only witnessed nature’s beauty and not its destructive forces. I had gotten used to the half-assed happiness very quickly when I was jolted out of this fantasy.

This time the dread to my existence came through my father; who is this fit guy with calf muscles of a Hindi tv show lead actor, which were earned by exercising, working out, eating healthy for the last 20 years. The guy is everybodys’ emergency contact. He had a heart attack in the middle of the night, right in the center of my fantasy land.

I sat on a train as they tried to pump open the arteries of my man’s heart. The bottom had fallen out of my world, a great void opened up in front of me. I hadn’t realized the responsibilities of being an older child, of having your emergency contact incapacitated and unapproachable, of holding up a tiny fort. I guess such people don’t get to cry, not often anyway. They have to be brave, in face of ICUs and hardly working hearts. But I am not, and never have been, a brave person. Foolhardy, yes, and certainly stubborn, but not brave.

In the last 27 days, I grew into the sock that was sewn for me. I spent my days in and out of hospitals, on unknown benches and beds, with books in my hand, crying and laughing when the opportunity presented itself, collecting stories to tell. And I have come out of the other side of the tunnel, dragging my father, our tiny fort, and all those stories along.

6

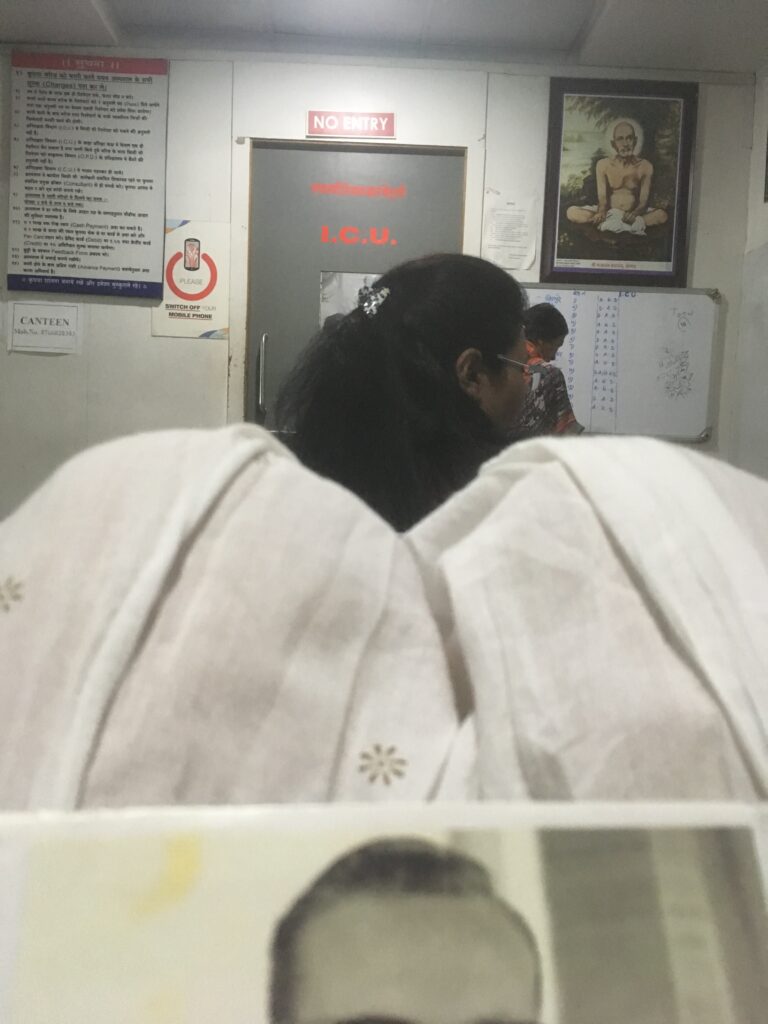

There were to be many days in the future in which I would find myself sitting outside ICUs. I would even come to have a routine and to feel not out-of-place here. And if I sat down to make a list of all my nights, I would probably remember more eventful ones, but as it was my first time outside an ICU, for a guy I had never seen take an injection, I suppose it deserves commemoration.

I had been protected against hospitals and ICUs all my life. When my Dada passed away, when my kaki had cancer, when Dadi got surgery, when kaki had cancer again, I had stayed home. These people had experience, mental modules, and coping mechanisms in place for hospitals. A virgin to those, into this delicately arranged world I walked one day.

I believe this is where, outside this first ICU, I learned to accept things for what they are instead of residing in the ‘why’s and the ‘what-ifs and not cry. And I would not cry next till I see my father’s beating heart on a doctor’s laptop screen and talk numbers. I slept or stayed awake on a bench reading Ruskin Bond using my mobile phone torch outside the ICU for 2 nights straight. Staying there seemed to be a refuge from the oppression of time, in which otherwise my mind wondered, dwelt on the worst-case scenarios.

I read Ruskin Bond talk about his father with fondness and about dealing with loss, from which I derived the strength I required. I picked him because my family is clumsy at expressing feelings, so except for secret tears they only had fake confidence, food, and physical proximity to offer. And they stayed with me on those benches, feeding me from time to time. There was no question of sleep but we stayed close for warmth and comfort. From the window, in front of the ICU, the world did not appear to be commonplace. There always seemed to be something drastic to be done about it.

5

What was I up against? Multiple blockages, a stent, mediocre medical facilities, the constant now-permanent ache in my chest & ideas in my head of what could have happened in the 12 hours preceding the heart attack when we assumed it was muscle pain. I was thankful too, for papa’s body’s capability to carry him for that long. The hardest thing, though, was to keep out of his head. How was he feeling? Was he scared? He had read his own medical report, what was he thinking? He did not have anyone to hold his hand, to tell a joke, to distract & tell him it will all be fine. What was he thinking?

Once in a while, I wanted to break down & cry. But we were a bunch of dominos standing one behind the other in a circle. If I cried, kaka, my trust-fall domino would have fallen with me. So I gulped down my sobs & did what needed to be done, wait. Sometimes I wanted to laugh from sheer relief. I went through the 5 stages of grief, multiple times & not in any particular order.

One night outside the ICU, when my skin had become an impression of the bench, they switched off the lights & locked us in. The room fell pitch dark. I have hated nights for as long as I can remember, but this one felt cozy like a soft blanket on goosebumpy skin. Everyone fell asleep one by one. I cried silently around 3 am. At 5, I understood the hype about sunrises. That day, Papa was shifted into a room. I could be in the same room as him. I slept on a sofa now. I do not remember feeling more comfortable in life before. At the top of my brain I still worried about what papa was thinking.

I still passed the ICU on my way to the room. I saw familiar faces on their regular spots; the old lady on the first bench, her daughter at the back. I saw many new faces too. It broke my heart. Not willing for papa to carry that weight, I finally mustered the courage to ask him what he was thinking and he told me what his stay in the ICU, around the man who broke his neck in an accident, the lady who got strangled by her own scarf, who was sitting on a chair unconscious for the lack of beds, had taught him; that so many problems, however infinitely varied they first appear, turn out to be matters of money.

4

Time halts in hospitals. Either that or it refuses to enter at all. And it makes up for the unsolicited absence when you step outside. Things go around faster than your ability to catch up with them like in a bad mystery novel. I did not sleep when I was home. I answered more than my fair share of calls for a lifetime. “We couldn’t believe it either, uncle. He was very fit indeed” I could console strangers in my sleep.

My father’s heart had multiple blockages. We were going to push a week before we could get him to another city. We had with us little bottles of SOS pills, in case he had an attack again. But don’t get distracted, this is my story, not his. I was in charge & at the end of my seat. I would look at the rise & fall of his chest, paying keen attention to his breathing while he slept. “No, he is not in pain uncle, not that he would tell” I would plan in my mind over & over scenarios of escape: What I would do after I plant that pill under his tongue, how I would get him to the hospital in the next two hours, from our home, from the railway station, from the train. “There is no reason to worry, uncle.”

I got to the next hospital without having to live my worst-case scenarios. This hospital shared a campus with a cinema hall & a confectionary store. Here is the most confused & eccentric I have seen time behave. The building had leftover mall decoration, big windows overlooking traffic jams, good-looking nurses, fish & relatives of patients. Here, a bunch of doctors would cut open the body that holds my pappa in it. There would be a 5% risk of losing him, we would be told beforehand. That was as far as I dared to think. “It’s a standard procedure and the doctors are very efficient”

In this puzzling time & space, we would remain-with our helpful analogies, entertaining well-wishers, traffic outside the window to assure us that the world goes on even if ours’ was on a break, with “I will ask him to take care. Thank you”, with pigeons to stare at in canteen walls. Silent suffering would go on within the shabby frame of the building. We would remain tossed away in a farther corner of it, where we lose our individualities in a wilderness of blurry people.

3

They took him in at 5 am. We were too stunned, too sleepy, too scared & awkward to know what to do. Being the only emotional one of the lot, I hugged him.

At 8 pm of the night before, we watched Sarabhai vs. Sarabhai, thinking our separate fears, not letting them touch the combined psyche. What does one do in the time impending an incident that can change your life?

At 9 pm, he did not take the anxiety pill that is given to nervous patients, said he wasn’t anxious. I still had a lot to learn about acceptance from this man.

At 6 am, they let us see him. His whole body was covered in Betadyn.

At 7:30, I imagined they made the first cut at the center of his chest. It is rather a lot for the imagination to cope with-especially when the imagination is a child’s.

8, relatives started to stream in.

9:15, I receded to the relatives crowding the waiting area. I wanted to be annoyed at them but was glad for the number of hands to hold, the people to hold my gaze. They told their stories from ICUs. Dadi claimed her mother came from heaven to take care of her in the ICU. She did not let the nurses’ touch dadi. Attya told us about the time her husband passed away in an ICU. He was at a wedding, he asked me to dress up she said.

By 12 I was too uneasy to sit still & listen. I started pacing around, looking for pants to buy online.

12:30, I was texting friends asking for assurance.

At 1 pm, I sat outside the movie theatre discussing books with cousins. The intensity of the experience seemed to be gradually disintegrating now in commonplace expression.

3, I was filled with a desperation not easy to place or classify.

3:30, the doctor came out to tell us that the operation was over. My father was stable.

3:35, For a moment it seemed a futile & presumptuous occupation to analyze, criticize & attempt to set things right anywhere. I left the building & broke down. I cried for what seemed like forever. A period of great turmoil had ended & was followed by uneasy calm- a sudden cessation of violent events, I felt the need to recover from the shock of what had happened & to look around to see who was missing.

At 11:30 pm, I slept for the first time in many many days.

2

The sky was bluer, the leaves, the grass greener & the birdsong sweeter. I was lightheaded. Even though it had been a long time since I saw the outside of a hospital. But the inside provided activity enough. It made me wonder why they never made a tv show based on a patients’ families’ life.

Episode#264, after what seemed like forever, they let me see papa in the ICU. He was attached to several machines. He was my papa & half in size. It was an easier world where I did not know people swole after operations. The moment weighed heavy on my heart & yet I was so happy to see him I could not contain it. I touched his hair to believe he was real.

Episode#364-#367, we wait all day to see him for 20 seconds during visiting hours. The fish in the waiting area, keep us company. Kaka & I play out a Kuch Kuch Hota Hai for fish. It allowed us to pretend everything was all right & get on with our lives. I hug everyone, try to hold people close.

Episode#368, A stray Ramesh Meshram stripped us of our 20 seconds. Mummy & R kill him.

Episode#402 Kaka gets me whisky before bed when time & opportunity permits. It fills my little life with so much joy.

Episode#458, They shift him to the HDU. One of us gets to sit next to him all day. R goes first, I replace her, we send mum in only for a few minutes, kaka only came to speak to the doctors. Mummy cooks, R or I fed papa, the nurses help him walk, machines assure us that he is alive. It is, on the whole, a very intricate mechanism of human relationships.

I carry my diary around. There is certainly no incentive to write, though there is enough reason to. I want to capture the song of steady beeping of the machines that have become background to our life. Episode#654, Papa makes elaborate analogies comparing the hospital to jail before he stops talking much. He makes the nurse pull a chair & asks to sit next to the window for a while, drains dangling from both his sides. It’s a beautiful view, I fill my heart with it, him at the window, outside which friends & familiars come & go, the earth still revolves around the sun, the world is once again in crisis, but the pigeon chirping in the canteen sounds optimistic about it all.

1

We rushed to a railway station as soon as we were let out of the hospital. We were excited about going home without admitting it, our collective psyche reverberated from it. We stepped onto the train looking for a different sort of life. And every click of the rails brought us closer to all that we had missed & were now coming back to reclaim as our own.

At home, we fell back into our daily routines, picked up our domestic problems right where we had dropped them, as though this existential struggle had been a frivolous distraction from tending to work projects, pet-puppies & soup-makers. Things had changed, no doubt: the house had to be sanitized, the ‘combat high’ we had donned had to be shed somehow, people had to be met & consoled, papa had to be assisted in bathing, walking & wearing clothes. I could not get myself to leave the house or answer calls. I was convinced getting married was the answer to my fresh insecurity. I emerged from my desolate night somehow; that is all I am willing to recall.

Now we continue to immerse ourselves in bad tv shows, movies & new projects, baby R demands to see fish, transforming my phone screen into an aquarium as a reminder of our past. On our 5 pm walks we open our tiny worlds completely to the tender sunlight, let the parrots, palm swiftlets & new flowers encompass us. Baby T’s banter accompanies me on the walks, cycling parallelly to me, he tells me about bites & itches, I prescribe oranges for mosquitos & watermelon for cats’. We growl our goodbyes at each other. Papa still keeps silently to himself. This is the most immobile I have seen him in life. This part of his temperament surprises me, because he never gave the impression of being a restless man, but he never did settle down.

Home suits our spirits. It’s our part of the earth. It is small & green, somewhat laidback, easy-going; fond of gossip, but tolerant of human foibles. We have spent a length of time here that lets us- savor the passing seasons, the change in foliage, the coming & going of people, & above all watch the children grow up. Living here, like being alive, has been testing on good days, and even on bad ones we enjoyed ourselves between troubles.

0

This is my last one from the hospital, about the hospital for a while. I often misuse Instagram when I feel like “I have to tell somebody about this or I would burst”, even though certain thoughts are strangled by expression. I have used writing to clear my mind, shift the burden and force an end to this phase of trouble in my mind.

Thank you for listening and for sending me kind messages. It was like a cast for my fractured heart. You saw me through this.