I hang upside down to the earth and my niece stands atop it, in her aerial drawing of us. In the drawing, it’s always daytime in India and I hang bat-like to the nights in the US. I’ve been hanging out–as a writing student in a small-town university campus in Arkansas–for eight months now. This place is so far and different from the small-town Maharashtrian town in India that used to be the whole world, that our imaginations had to be expanded to accommodate it. We added an extra clock displaying CST on my parents’ wall, so Mummy may stop calling me in the middle of the night. I set up zoom science lessons and youtube videos for my niece to understand the rules of the solar system, the shape of our world, and the concept of white people.

Yet, I wouldn’t be able to tell you which side of the earth I am on when I sit in a Starbucks working on my laptop. The Starbucks in my small-town American campus and the one in my small-town home have the same backdrop of English pop songs, standardized interiors, and coffee. It is a portal that connects me a brown writer–with an Indian accent adding diversity to the white world–and the privileged, fair-skinned, English-speaking, coffee-drinking and virtually working Prachi in India through its free wifi. It is only if I shift my focus from the screen that I see the color (colorlessness) of the people around me or hear someone say Chai Tea that I am jerked back to my 11 hours-lagging, upside-down reality.

“What’s the most difficult part of living in the US?” people here and back home like to ask me. Some of them, I believe, are trying to calibrate their #Wanderlust hopes and regrets. But most are just looking for another immigrant-experience-shaped peg that fits the Immigrant Worldview shaped hole in their minds.

My answers changed as months pass. I struggled with feeling safe and trusting people the first month if you can call such adjustments a struggle. I was so far from everyone and everything I knew, I didn’t know how to live. Shortly after finding friends, I was irritated at the US documentation procedures, housing, and the commute. Then with other human things that make up a life.

In reality, I don’t think I struggled much because of the change. I am the ideal colonized minority–I already spoke the colonizers’ language, read their books, saw their reality tv shows, so dressed like them, and felt invested in their presidential elections–so coming here was a homecoming. But people don’t like to hear that. Over eight months, I have learned to wrap my immigrant experiences in struggle blankets with humor and drama. It distracts people so I don’t have to shove my life through holes it doesn’t fit.

The food here is bland. Having to cook triggered disordered eating a few times in the last eight months (but it wasn’t anything I couldn’t manage.) “I miss cheap Indian street food! You colonized nations for spices and teas. USE THEM” I yell at people. Mobility is problematic. How nations function without autos, rickshaws, ST buses, or trains makes no sense to me. Seeing my grandmother should not require a check-in, security, and hundreds of dollars. The individualistic and solitary way of life is very different than how I live in India, sharing a room with three others, all dependent on each other for basic functioning. It’s easier to afford privacy here. “There is so much quiet, I can hear your own thoughts! I am not sure how to feel about that.” Here, I can invite touch, hugs, and kisses into my privacy, whereas they are abundantly bestowed without asking in India. None of these are struggles; not yet.

‘Struggle’ is too big a word for a few skipped meals, a periodically empty bank account, or missing people you love as long as they are safe. These are mere matters of mental housekeeping. A struggle uproots you. I struggled to breathe when mummy tried to strangle me as punishment for being bad at studies. I struggled to enter the asylum and face mummy for five years. I struggled to look into the mirror after being bullied for how I spoke, looked, and dressed. It’s a struggle to navigate my phone gallery because I am scared of hearing kaki’s voice in there. I struggle to admit that we let her die. But the moody weather and bland food are just administrative details to work around.

But that’s not the answer people are looking for. So I reach for the more palatable bits of adjustment to present to them. I search for the ones that look mendable–the kind people can sigh and say they are sorry about–offering them a sense of power to set things right or set themselves apart from the bigots.

“I struggle to get coffee” I oblige.

No waitress, cashier, or coffee maker has either heard my name or pronounced it right. I have never heard a resounding PRACHI before the thump of an Americano on a counter in a Starbucks. It usually goes like EMMMA, ADAAM, . . .BETHANY. . . Americano for <soft mumble mumble>. . . The Americano then sits on the counter, unnoticed and unclaimed, till I realize that I am the mumble mumble who it is meant for. The Americano usually ages from hot to warm by the time I get to it.

Six months ago, I considered getting myself a name tag. Then I said things like “PRA rhymes with BRA, CHI like in CHIcken” which just confused people more. For a while, I considered donning a white-person name for coffee-buying purposes. But I don’t have the accent for it. Now, I just spell my name Pee – Are – Aye – See – Eh – Eye to the barista and hope for the best.

Over eight months, I am beginning to see the linguistic differences that cause the confusion. The way I pronounce P, also called the Indian way, is closer to a प (/pə/), is softer while the American P sounds like फ़ (pha). My T is ट (as in Tip) and theirs is ठ (as in Thatch). They have two different व sounds–W and V–that sound the same to me. So, they hear my pronunciation of P, R, A, C, H, I as whatever the sound, shape of my lips, the motion of my tongue, and force of the air leaving my mouth denotes to them. It’s an honest mistake. And now my ears have learned to stand at most variations of my name.

Other socio-cultural differences that make great stand-in struggles: the toilet paper and the jet spray, processed foods, and fresh produce, Trump bigotry and Modi bigotry, social security, and cost of living. The one I am currently making sense of is Caste and Language.

In the place where Indian applications and forms ask for my caste, the US ones want to know what my country of birth and first language are. The college, Visa, and social security applications offer a drop-down of possible language-shaped pegs to put in the first-language-shaped hole.

My birth certificate states my caste and country of birth, but I don’t know what my first language is. I’ve been struggling to deduce it. When asked, Google, it spews a bunch of options–the native/mother tongue, the language you are familiar with since birth, the one you are best accustomed to speaking.

Is my native language the language of my forefathers or the language my grandparents spoke? The language changed many shades since my great-grandparents immigrated to a state with a different local language. The language my grandparents and parents spoke is a shade between real Rajasthani Marwadi and colloquial Marathi. Mummy’s Marwadi sounds different than mine or papa’s because we were all raised in different parts of Maharashtra.

Is Marwadi even Mummy’s native language if her parents talk to each other in upper-class Marathi? Is it papa’s if he was raised by a Marathi boarding school more than his parents? What is mine if I speak with my father in Marwadi and he responds in Hindi for thirty years? A time so long we don’t realize we are speaking and hearing different languages unless someone points it out. What is his first language if he speaks with his wife and daughters in Hindi, but his mother and siblings in Marwadi?

Honestly, I grew up around Marathi more than I did Marwadi. My friends, our maids, neighbors, teachers, drivers, books, and radios spoke in Marathi, although in different dialects. I usually pick a dialect based on who I am talking to–upper-class dialect with teachers and officers, papa’s rural Marathi with rickshaw drivers, shopkeepers, and domestic workers. The dialects make me an in-group and win me favors. What is my first language if Marathi is more familiar, my ancestors spoke Marwadi, whereas Modi told me it should be Hindi. I’ve been using Hindi to obey the political bullies that are in charge of violence.

Do pidgin-babble-shaped pegs fit in first-language-shaped holes?

Your first language is the language you think in, my friend offers.

Marwadi for family, Hindi for family-friends, Marathis for domestic work, and English for work work and friends. English and Marathi for doctors and therapists. English and Marwadi for siblings.

Can I fit a people-shaped peg in a language-shaped hole?

No no no, don’t code-switch, said the psychiatrist at my uncle’s party with distaste. It disturbs him to see people switch languages in the middle of sentences. Especially the people from my town, he tells me, start sentences in Hindi, pull in English words, and end them in Marathi. We should all spend at least 10 minutes each day consciously only speaking one language, not a single word from another language. We should make this a compulsory exercise for our kids. It saves brains from lazily patchworking languages.

Fine, no code-switching. Maybe I should go back to the pure Rajasthani Marwadi for pidgins and derivative language-shaped pegs that look ugly in first language-shaped holes. If purity is the goal, is Sanskrit, Latin, or Persian my first language, for at least 10 minutes each day?

First language: Indo-Aryan/Germanic

Am I allowed to put murky and evolving identity-shaped pegs in purist holes?

I am reminded of something my 10th-grade history teacher once said to me. Your first language is the one you argue in. It’s the language that triggered thoughts and passionate feelings melt into when caught off-guard.

English! My first language is English. I could never call someone an bitch, asshole, piece of shit, mother f****r, d**k in any of the other languages. I don’t know even know how to say Schizophrenia, Trauma, Therapy, or Feminism in them. And there’s no fighting without those.

I see English right at the top in the drop-down menu and it fits perfectly in the furious little first-language-shaped hole.

*

The university office sent back my proud little English peg from the first language-shaped hole of their application form. Asshole, son of a bitch I yell in explanation. But English isn’t mine to claim or keep. You have to be born with it or fight to earn it.

I tried to map the veins of English through my life hoping it would convince them to let me claim it.

Mummy wasn’t born in English. But she learned to read, speak and think in English when she was little. She was schooled in English and found her favorite stories in English books. She read and loved P.G. Wodehouse, and often veiled Mills and Boons in them, also in English. But then she got sick. The asylums and homes she was sent to treated her in Marathi. I think one can treat a language off a tongue over decades. Between the asylum and her husband, who was neither raised nor educated in English, Mummy only retained enough English for short-hand emergency texts.

“R call me sick,” says her message on my phone when I wake up. It unpacks into an anxious request when unfolded “R called me. She is sick. Can you please talk to her?”

Papa journeyed the English current in the opposite direction of Mummy. He was born too poor to ever see or touch English growing up. However, a scholarship picked him up from his Marathi school and dumped him into an English college as an adult. This Science and Mathematics prodigy, now humbled by English, sat teary-eyed and hungry on the last bench of his class. He was too dependent on success for survival, and could not afford to fail, so he didn’t. He learned enough English to hold on to Maths and Science, got a post-graduate degree, and become a government officer.

“Beautiful car. love u beta” Now he uses English to react to things on social media and convey operational instructions to his employees.

In all of this, I didn’t get to be born into English either. Mummy had lost most of hers and Papa hadn’t found enough when I was growing up. My small-town English teacher, also raised in Marathi schools, never knew enough English to please the psychiatrist, even for 10 minutes.

English was introduced to me in the form of a weapon. Access to English, pure or pidgin, was the cause and weapon of bullying in schools. The English I learned from reading Mummy’s books was bullied off my tongue by peers who had no access to them. And what was left of the English on my tongue was disgusting to the people with similar access.

“Don’t talk to my daughter in English, I don’t want her to get confused or pick up incorrect grammar” my aunt said to me one summer.

I wasn’t born in English, but my family traversed lives in it. We fought, cried, loved, and muted in it. So, English isn’t my first language, it is probably the measure of my life. I am sure I can move things around. English first; thoughts, anger, music, laughter, and people secondary. English – first language, Prachi – secondary person.

A Prachi-shaped peg in a pristine English-shaped hole.

I was sent to an English tutor after swimming. He said some version of “singular Noun will have a plural verb. gerunds follow. . .” to put me to sleep. But he spoke to me every day. Then someone told me to watch English tv shows. It took me two years to get interested in stories that I couldn’t make sense of. Another 2 years to realize that understanding a fluently spoken language does not translate into an ability to speak it on the listener’s tongue. So I took myself to rich people’s schools. I started speaking with people in English. I started writing too. I cried in English till I found my way to happier words.

I haven’t discarded my Marwadi, Marathi, and Hindi. Some of my cousins and their parents have surrendered all of theirs in service of English at the school teacher’s advice. Her parents’ messages come fully formed and punctuated. But neither I nor my parents can afford to mix up mama, kakas, attyas, masis, nana, dada, nani, and dadis into uncles, aunts, and grandparents. Their love and care for me are too dissimilar to fit into the same word. I can’t fit my dadi’s grand acceptance in the same grandma as my nani’s bullying. I can’t lose the motherlike sounds of mama, mami to uncle and aunt. They raised me in a very different way than my kaka, kaki kept me floating.

So I keep the differences stuck to the back of my throat. I bring them out to converse with my upside-down, 11 hours-lagging world. I use them to hold people close–the people who help around the house are maushis and kakas. And they speak to me like relatives, joking, scolding, worrying, sharing food, and gossip. It is this jagged edge that doesn’t fit the acceptance-shaped hole.

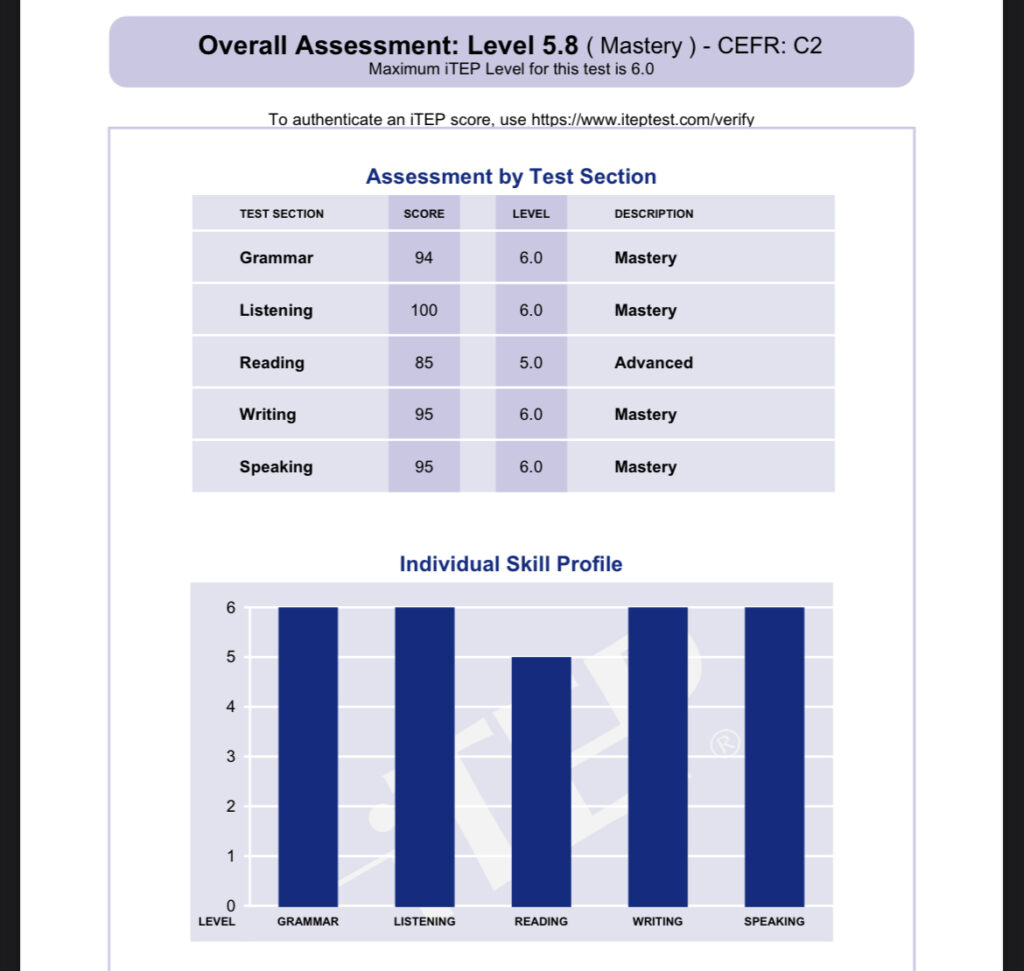

But I must don English, structure and form, grammar and accent, sounds and lack thereof, to fit in. So the governments and democracies involve themselves in bestowing my first language to me. I, and some others from the poor schools of poor countries, go through professors who make fun of how we pronounce the S (स) in Arkansas, where we add articles in a sentence to wash off the impurities it off our tongues. People who don’t need such purification to win their snug places in the English holes, battle GREs, TOEFLs, and other exams–which are just minor administrative details, don’t be dramatic–to prove that they can fight in the language they cry in.