1

We lost her often, to hospitals, train stations, and anonymous hiding places. One time I lost her at a new hospital. I walked into the corridor in my new sandals that went ktch ktch on the floor drowning mummy’s screams from the room. A big girl ktch ktch, in almost heels, at 4. Then there was the time I have a photo of. I am in a borrowed red and white dress, at a stranger’s house, where papa found us; after I cut my birthday cake. It was mostly after being found that I realized that one of us was lost.

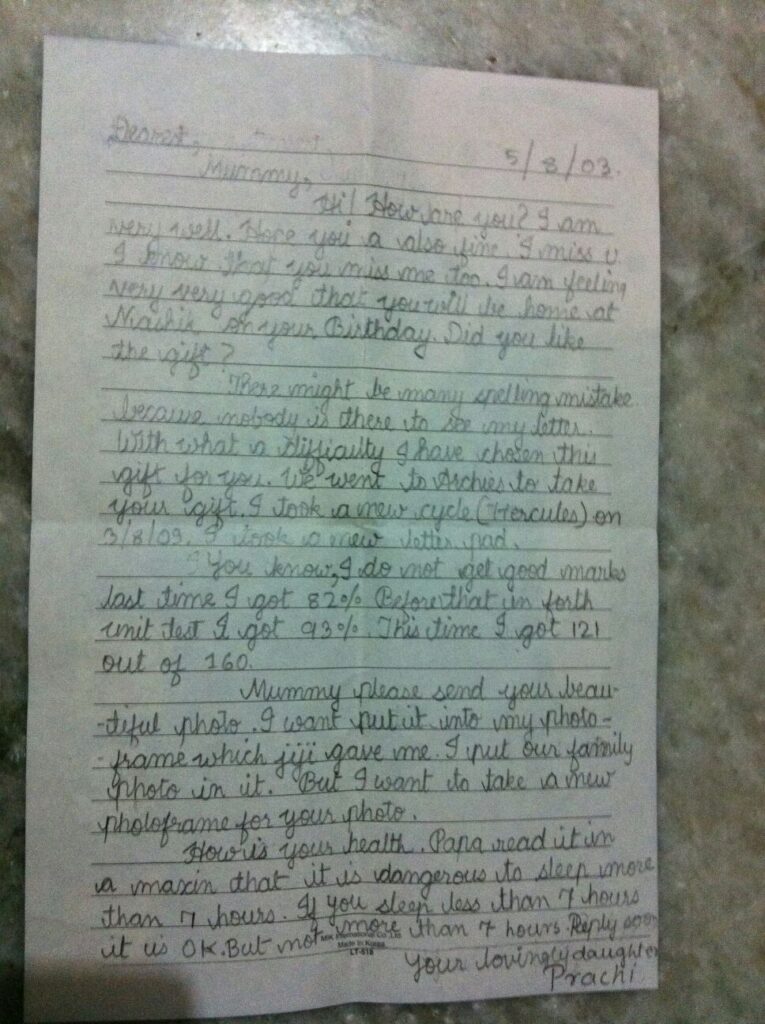

Then I lost her, not in a lost-and-found way, to the asylum. The loss solidified when I wrote a letter to her, on a self-bought letter pad with bunnies on it, without any adult supervision. More still when I visited her in the asylum where she wore all white and yelled at the counselor. It grew porky spikes when I was punished for not doing homework for the first time. The phone calls with her on which we cried tied up the loose bits and made the loss whole.

Loss is deeper, heavier when it isn’t final, without a ‘best by’ date, without a cause to point at and say ‘that’s why!’; for in that state it mixes with hope and becomes lethal. Loss becomes bigger, gravitational when you think it was your fault. You point at your chest and this ‘that’s why?’. At 10, I discovered that loss is like a black hole, with infinite density at zero volume.

3 years later, just when the loss had become an over-worn shoe- uncomfortable but familiar- I lost her again. She came home in olive green and black saree. I tiptoed out of my hiding to check if she was real. After a fair inspection, I hugged and kissed her. And she pushed me away.

No one teaches you how to react to a mother mysteriously returning from a black hole without any love for you. I lost the mummy who was a friend, a teammate, who did and liked PDA. But this mummy was better than the idea of a mummy suffering, being given electric shocks, in a faraway white-wearing world. Is it better than not having a Mummy at all? I don’t know. Loss grows in dimensions when compared to possible losses.

I decided to like the woman my mumma had become away from me. I broke her into parts and decided to like each one with TLC. She had my sense of humor, she was emotional and receptive. She could be militant about trivialities and ate all my snacks, but that could be overlooked. Eventually, I could categorize the parts: some sick, some hereditary coping mechanisms, and under those blue-black tissues were the good, funny, very irritatingly naughty parts. These parts would become my mental armor for when the sick and violent parts took over, which it did often.

Loss can be broken into pieces. The sum of all the pieces of loss is greater than it was whole.

2.

When I came home, I took charge of the “bad” parts. I spoke to her when she was at a railway station, I spoke to her doctors in secret and conspired to get medicines into her; all jobs that papa did for the last 25 years. I also started to mother her like hers’ never had: kindly.

I read her mental health coping stories when she was well. I held her hand and let her discover her own mental health instead of imposing, electronic shock and blackmailing her into acceptance. I encouraged her and was proud of her every time she identified a sick part and let it be nursed into health.

I let my mind widen to make space for this new experience, of a mumma aware of her sickness, of a mummy who didn’t have to be followed into the washroom to check if she puked her medicines. I would risk walking a minefield of triggers. I would be triggered more often than my body knew it could take. I would grow a new kind of courage, the kind that had space for hope.

I started building a relationship with the “good” her. This new Mummy, I decided, would be equal. I could call her Nalayak. And I would, when she put sindoor in my hair for no reason or when she licked my cheek under the ruse of giving me a kiss. I decided too that I could smack her butt if she was bending. She decided to be the irritating sibling R had recently stopped being. She would lay diagonally in my bed at night. She would buy me gin on my birthday and drink a Breezer on papa’s, forgetting that even the mention of alcohol was a childhood wrecking trigger.

I would always reply with a “isn’t it too early to start drinking ma?” “whiskey or vodka?” “My stash is over, ask papa” when she mimed for a glass of water during lunch. I would teach her to say nice things, something her mother considered a weakness, an infection.

None of this made up for a life spent in fear and craving, and I wasn’t expecting it to. I wanted it to be what it was, the best hand I could make from the crap cards I was dealt. And it was phenomenal.

Then I lost it, last month.

3.

She was teaching a little boy Maths in the living room. The yelling woke me up. I don’t remember anything after the sound of scolding- the crushing of a little spinal cord with the guilt of causing pain, the talk of hitting- before I fell… into the vortex; A vortex I knew like the back of my hand, that I was nonetheless unarmed to traverse. In the span of 30 seconds, it took me to Nasik 25 years in the past.

I am 4. I beg Nana-nani to not leave the house, she’ll beat me, I assure them. Nani considers but leaves when mummy asks them to. I am alone, with her. Mummy has the multiplication table of two written on the back of nana’s discarded legal document. She asks me questions. My mind- including the part reserved for logic and maths- is filled with fear and helplessness. I have been answering all her questions wrong. Each wrong answer is followed by a slap, a punch, or a strangling of the throat. The weapons- footwear, kitchen utensils, tv remote control- change as I retreat deeper into the house and myself.

I am hiding under a pastel pink study table. She asks me what 2 twos are? I want to say 4 or 6. I weigh both the words on my tongue. Which one sounds like it could save me? 4 comes to mind first, so I distrust it. I quiver a soft 6. It does not save me. She picks up nana’s chappal to hit me now. I can’t breathe. My chest hurts from gagging, from the desperate drawing of breaths through dense sobs. My gut pulls the air, with it the lump in my throat travels to my chest and gets stuck.

The room is losing color, turning dark around the corners. I am not sure where I am- inside or outside the vortex. There is nothing to feel, hear or touch but static, in a language I can’t make sense of.

Then I feel something. A body, It’s mine, it is 28 years old. It is…I am yelling, at someone, about something. Now, I am crying. Everyone outside me has spikes. They wage war on me. The war is in my body, in my study, which is not dark, not dangerous, but is.

The chest ache traveled with me. A 28-year body, with a 5-year-old’s chest ache. My insides are still pulling on themselves. They stink of fear. A fear that is primal, that comes from the core of my being, the kind that makes a human cut her own leg to keep surviving. It has been a truthful companion for 23 years. It stuck with me through my misdiagnosed asthma medication, even though the FC Road doctor’s “second- woman- heart at the center that tends to hurt”; 23 years later not be unaffected by.

Like a benevolent guardian, it showed up before each exam, after each breakup, after a tattoo gone wrong, after watching the mother-child-separation scene in Dumbo. When a friend left, it took to a tree at Pune university to cry. A tree that looked old enough to withhold the weight of this loss and all the others. That time – when my mind became mummy’s hospital bathroom, looking over the toilet pot for remains of medicines as mummy threatens to hit people, making my chest a ticking timebomb- on the stage at my theater practice. I returned to the room sobbing, curled in on myself, people unblinkingly stared and in a corner, my friend cried with me. When over a call mummy said, “you have to save me. Come get me before they hurt me” making me collapse from the restaurant’s blue washroom into those electrocuting rooms “P…you have to save me. It’s you and me against the world, baby” overlapping with “they will hurt you after they are done with me” overlapping with “they can see us through the tv” till it becomes a blinding, buzzing white noise that enveloped me. I am here to take care of you, help you survive, it seems to imply. The chest ache is a memory of a memory of a memory of a memory that my body preserved in its spinal cord.

Faced with danger, in the confusion between fight or flight, my spinal cord decides to act dead. Still gathering ammunition- sugar and water- bourbon biscuits, drinking water, sweating palms, fast breaths, and SOS pills. The Olympics of surviving, looking for a tangible thing to touch, smell, and see as proof that “THIS is real”. The SOS pill is made of magic. It turns chest-aching sobs into chest-aching shivers while I fall in and out of consciousness. Then it turns everything to haze, which also hurts my chest. Eventually, it makes the haze solid things. They move around- sometimes as mummy yelling through the door, sometimes a cliff I am being pushed off of, and sometimes they become a nudge without a body, throwing my forehead on the bed-side-table, splitting the soft skin open.

Each PTSD episode is a journey through the vortex, via the forest of the spirits and the devil’s snare of ache and darkness, ending in blood, in my bed. I have gone on this journey innumerable times since I was 7. One day I hope to win this game of Minesweeper; defeat my spinal cord and forget this fantasy trip through cupboards and train-station platforms into a world of pain and fear; a secluded experience and fall in step with the world that continues to want degrees, labels, productivity.

4.

I have been the P that started crying in a wine bar after seeing a couple she barely knew as friend’s friends. How the lady, from a difficult childhood, had been found by normalcy and love. How I envied her everything! And I have been that P who said to papa “this may be the wrong move to make. It may lead me to take financial help from you. You advise against it. But I cannot work with a manager who disrespects and gaslights me. I hope you understand.” An “I hope you understand” Not an “I am sorry, is this going to be okay? Not “no I didn’t quit even after he said this because I don’t want to be (be seen as) unemployed.

One best decision of life at a time, I became 28. Rooted me in me, shifting the locus of my control inside me, my psychology book from sem 4 would say. I had put 25 years between P with a victim complex, catastrophic tendencies and the P that is anchored in herself. It had taken me 10 years and many gallons of tears to do so.

10 years to understand, accept and forgive the existence of Brute Luck, Love, Abandonment, Violence, Happy. It took the very last bit of my energy to stop comparing myself to people, to stop wanting to be them, or just be liked by them, to stop crying at the fancy bar after seeing your friend’s friend, who found love. To stop wanting everything that belonged to them. To stop my tears from mixing in my beer.

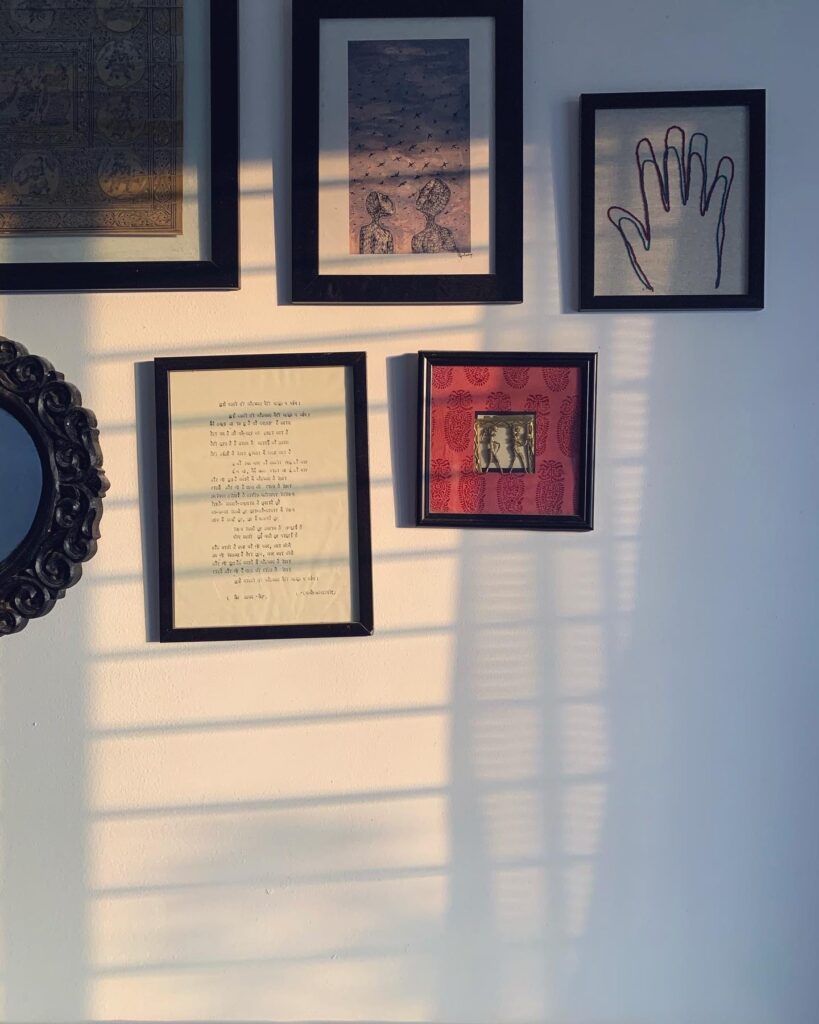

I lost her again, didn’t I? I also lost 10 years. The foundation I had built out of the non-sick pieces of mumma- her lame jokes, the breathless laughter, her love for Goldie, her love for beautifully crafted sentences- of her good human-ness, that loves me, thinks me worthy of love came crumbling down on me. I stopped staying in my study. I lost my “home” too.

You can break loss into pieces, but its sum too is bigger than the sum of these parts.

5

I am not holding it against her. I can’t. I have been her. I know where the bile comes from, and what it can make humans do. To whom evil is done do evil in return, right? She, and I, were dealt bad cards. And hers are worse than mine by any measure. We are trying our best to not become what was done to us; acting out the lack of coping mechanisms in face of crippling fear. One can be angry at choices, how can one be angry at involuntary acts of survival? Even our classist law forgives self-defense.

So, it’s not anger I carry, it’s exhaustion, that pins me to the floor, immobile, unable to carry the losses anymore. How can you lose someone more than you ever had them?

6

I am tired.

I am tired.

I am tired.

I am tired.

7.

I dislike Mumma. It’s a heavy dislike- not like the dislike of spinach but like dislike of chocolate, heavier, angrier. And no I don’t hate her. I simply cannot get myself to like her. It took me a while to be around her again; longer to say my first sentence to her “I put it in the fridge.”

The chest ache is a visitor. It comes every time I hear loud voices. I still hear cries and screams that do not exist. I grit my teeth at any animal sound. Animal’s pain/suffering, and stories from the holocaust and apartheid are the spare keys to the vortex. I weep as I write this. But I don’t cry while rewriting it. Every day I get further from the vortex. It becomes harder to imagine or remember the sticky heaviness that lives inside it. I remember the sufferers, even the suffering, but I can’t feel it; I can’t find the thing pointing to which I can say “this is what hurts. This is why you feel this much.” As my mind-body acclimatizes to the outside, the feelings of the inside seem like a gross over-reaction. This too, an evolutionary survival mechanism for sanity?

“I hope to learn from the revolution, remember the vortex, and learn to fight the summoners next time. But this survival mechanism leads me astray. So the next time a trigger still feels like a bullet. It knocks me out, I fall to my knees and rediscover the vortex-like I never knew it.” I complain to my therapist.

“But that’s not really true, is it?” she asks me.

I started seeing her 6 years ago, after my first PTSD episode as an adult. Scared of the violence that the triggered P is capable of- walking into a rainy night, in an unsafe area, crying, stubbing a cigarette on myself, breaking coffee mugs, imagining violent deaths, like an animal stuck in a barbed wire. Recovering to feel embarrassed and ashamed, in a living room that was safe after all, at least physically.

For the next 3 years, I sat on her sofa- after getting triggered- staring at the ceiling, yelling “I give up, I can’t leave this clinic, I am scared. I want to stop existing. Please” clutching my chest-for 55 minutes before leaving. Then I became capable of sitting with my triggered PTSD without causing harm, to myself or others. I stopped wishing to stay in the clinic forever. Last year, I found a dull hope where triggered helplessness and rage were. “It passed the last time. You didn’t think it would, yet it did. It may pass this time too. Don’t give up yet” it seemed to say, confidently.

A human brain’s capacity for memory and its plasticity are a blessing. After months of training my body in breathing (literally breathing) I can make the hope stay for seconds. This time grants me humanness enough to reach out, with my voice and mind, to people. It has expanded me and made me capable of trusting some people to hold me through the vortex, without fearing that they will abandon me. I let people in. It’s a game-changer.

Now in a PTSD episode, I take my SOS pill and isolate myself from more triggers and people I may hurt. I text friends. They stay with me. Once, H stayed with me in a rickshaw in Pune, over a call from Canada, spoke me into an open-air cafe, and told the waiter to get me water. D stays online virtually holding my hand. Prag assures me that it’ll pass, almost directly addressing the fear.

When I recover, I reach out to M or Doctor to see if we can fix a glitch in the system that harbors Mumma’s or my triggers. Once I figure out, I tell my friends what happened, why it happened, and what helped. I course-correct. I tell them to not leave when I look like I want to hurt them; it is my body’s way of defense, to seem like an attacker. I relate helpful discoveries: touch and hugs are reassuring, they anchor my mind in the present physical space outside the vortex but if I ask for distance, leave me alone.

They are a small ‘P’s army’. They hold me and I promise to hold them every time one of us falls into our personal vortex. Till I reach here- my journal entry from yesterday: I wake up to her teaching the boy every day. I carry my heart-lump to the study. I try to accept her as a whole. I let her sit in my bed today. We threw pillows at each other. She giggled like a child. I realized that I still love her laugh. She asked me “Did that hurt your feelings?” after a harmless joke. I am going to let myself like her a little bit.

6 years, 24 days, 1050 hours, 180 mg of medicines every day, trained professionals, an army fought with and for, eventually remind you that coming back is not the same as never having left. The journey changes you.